Jodie Cavalier, to dream [in spanish]

An exhibition at Labor is a Medium

On view October 22–November 19, 2022

1183 DeMeo St, Santa Rosa, CA

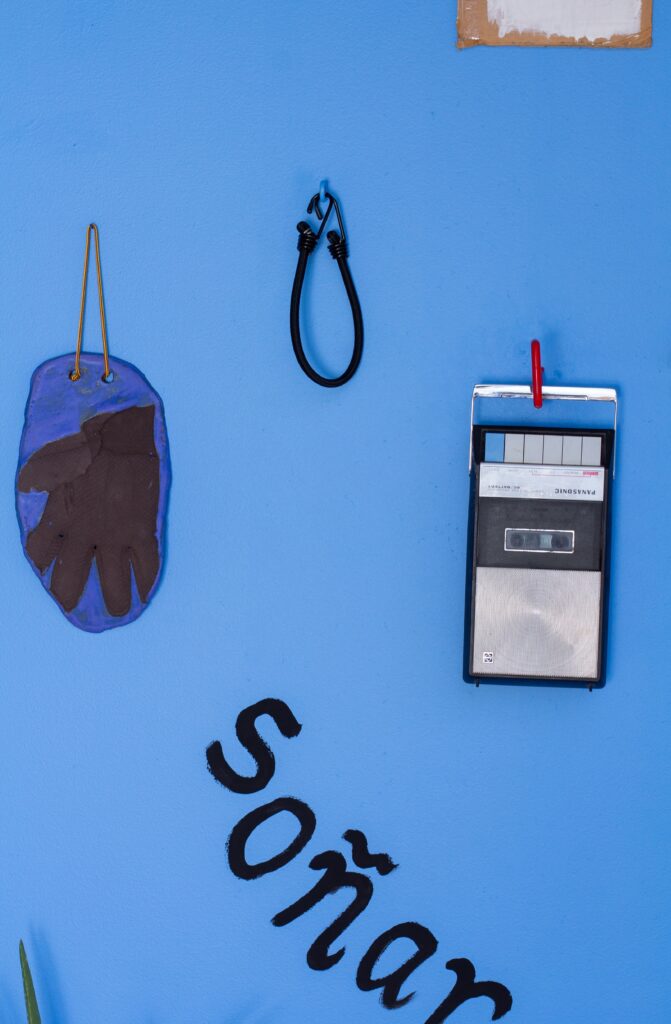

In to dream [in spanish] Jodie Cavalier takes visual cues from Mexican street vendors, farm laborers, taco trucks, and construction lunch break sites to present a collection of handmade and altered objects. Tools made from ceramics, brooms, pamphlets, found objects, toys, and food combine to create a moving sculpture that layers work, home, commerce, migration, and play into the same space; a space that might make sense as something like a dream in another language, her ancestors’ tongue.

Consider a Desert; a Bar of Chocolate

By Daniel J Glendening

A friend and I once boarded an Amtrak train, hid in the bathroom until it left the station, and then rode in the viewing car from Davis, California, to Colorado. Nobody asked us for tickets, and we didn’t have any. In my memory the voyage lingers only as fleeting images. I was sitting in the viewing car looking out the window as the sun rose one morning—we were traveling through the salt flats, the sheen of water stretching in all directions catching the golden light of the rising sun. A flock of birds lifted and skimmed across the wet ground. In the far distance, the horizon was punctuated by jagged mountains, deep blue in morning dark.

There are places like this, where the world seems to go on and on, endlessly, like an ocean, unbreaking, unchanging, stretching toward infinity.

In her poem, “An Island,” collected in her recent publication, Fool’s Gold, Jodie Cavalier writes:

You see

I grew up in the mojave desert

flat, dry land for as far as you can see

and as far as you could possibly imagine

the only water we saw were mirages

“can you see it?! do you see it too,” my sister would say

as she knocked her fist against my arm

Endlessness. Infinite. Unfathomable.

The desert of popular American imagination—bulbous cacti and an idiotic coyote; the paeans to western expansion of Bierstadt’s canvases; Captain Steve Hiller dragging the corpse of an extraterrestrial, wrapped in his parachute, across the flats, jagged peaks in the distance; the snow-capped ridges and violent sunsets that form the backdrop of Arthur Morgan’s killing sprees—all of these landscapes are engineered mirages. The desert is not any of these things.

Consider a bar of chocolate, shimmering with a scaled surface of salt-crystals collected from the Utah salt-plains. One could take the desert into oneself. One could close the eyes, open the mouth, and lay salt-crusted chocolate upon the tongue in an act of worldly transubstantiation. One might take the desert into oneself and thus, in a sense, one might become the desert, too.

Jodie is from the desert; she grew up there, in the Mojave. A place that occupies an imaginary, essential concept can also be a home. This is the point—a point of slippage, of one-thing-becoming-another-thing—in which Jodie often works. The desert becomes chocolate, and the chocolate becomes you. A snake—alarming and wondrous—becomes a stick. Grief becomes joy, hope, and humor. A shared meal becomes a transference of knowledge; food becomes life, becomes a mantra, becomes an act of political resistance.

Jodie’s work is, in some ways, difficult to write about, because it’s difficult to tease a single thread out from the whole. If I write, then, about food—about her letterpress edition “I Want Food”; about her tamale-making workshops; her dinners; or the frozen ready-to-eat meals she and her partner produce at scale to stock Portland free-fridges—then what of the object? If I write then of the objects—the hand-made ceramic interpretations of her grandfather’s tools; the delicate mobiles of pocketed detritus; the ragged, torn tarp dusty with desert sand, used in the process of freeing a stuck car on a road somewhere in Utah—what then of her poetry? And if I write about her poetry—”waiting for the heat to pass / waiting for feelings I have never felt”; poems on napkins, in books sandwiched in clay, divided, spanning time—what then of this video of the sky breathing, this exhibition of brooms, these postcards sent with no return address? Jodie’s work is a kaleidoscope: turned this way just so and all the pieces fall into place as one mandala; turn some more and they disperse, a thousand disparate reflections of each other. And it’s beautiful either way.

The term that occurs to me now, suddenly, is spaciousness. Again, we return to that land that stretches “as far as you could possibly imagine.” In Jodie’s work is a profound sense of spaciousness: of perceived emptiness, of large distances sparingly punctuated; a sense of time stretching out in all directions; of quietude; of a gulf between what is and what could be or could have been. In her delicate wire mobiles, hung with detritus from her pockets—a receipt from a convenience store, a dried orange peel, a small piece of rope, a bottlecap—particular objects tied to specific places and memories are suspended, the distance between them moving with the breeze; the wire almost disappears. Some span of days links these objects to the moment of seeing; as a viewer, that span is unknowable. For Jodie, that span is specific and of memory.

Speaking broadly, there is a gap between the artist and the art-viewer that can never truly be bridged. What is seen is, often, not what exists. Art is, in a sense, a mirage. It’s a stick perceived as a snake. Many artists strive to overcome that gap; to close it; to generate a direct line of communication between themselves and their audience. Jodie seems to revel in that space. She leaves gaps intentionally—spaces for a viewer to step into, sit, and reflect awhile. She has mentioned that a large part of how she makes work is spending time sitting and thinking. Time resolves questions, if we let it.

For her recent exhibition, Fool’s Gold, Jodie presented a body of work that included objects from her late Grandfather’s workshop in the Mojave, along with sculptures made as replicas, or simulacra, of various tools her Grandfather worked with. There is a rake-like object with prongs splayed wildly, an oversized horseshoe glazed indigo and hung from knotted bootlaces. There is a sense of the man as a tinkerer, a repairer, one who made do. Her Grandfather likely labored his entire life, though that labor was likely undervalued; his tools, now, transfigured into objects that defy use.

Let us expand the notion of labor as a desert: as a vast space, home to many things, each working in concert with one another to produce a complex web of exchange, and of life; as distance between two things, spanned by invisible linkages of time and space; as a place to sit, in the sun, and think for awhile, about everything and nothing at all. Like Connie Zheng’s wasteland, Jodie’s desert is labeled as largely unproductive under capitalism, its designated usefulness seemingly confined to simulations of war and rehearsals of violence. This ignores life, space, and dreaming.

If productivity is a predeterminate for value, I say abolish productivity. Let the desert be what it is, which is ample and many. Let us tinker and through our tinkering imagine, dream. Let us claim our labor for ourselves, and claim whatever we will as our labor: thinking, dreaming, imagining, sitting and doing what looks like nothing at all. It is enough to simply be, sitting in the sun, hand in hand with one another, dreaming the world anew.